Back in the Game: How to Return to Profitability

The Growth Dilemma: Opportunities Versus Challenges

Construction demonstrates the ultimate comparison. Will it be gluttony, or starvation? For the better part of the last 10 to 15 years — minus a short disruption from COVID-19 — the industry has seen unbridled growth in nearly every sector. Construction organizations seem to have no shortage of opportunities, and revenue growth often resembles a runaway train, accelerating ever northward.

Reflecting on recessionary times makes most leaders sick and seem desperate. Additionally, for at least the past four decades, leaders have opined about the lack of talent facing the industry, with countless studies describing the overall lack of trades, supervision and management personnel.

Organizations must grow strategically and not simply answer every client demand or proposal. Doing so may be to the detriment of your long-term strategy. There must be a fact-based approach to decision-making that connects to more than just gut-feel.

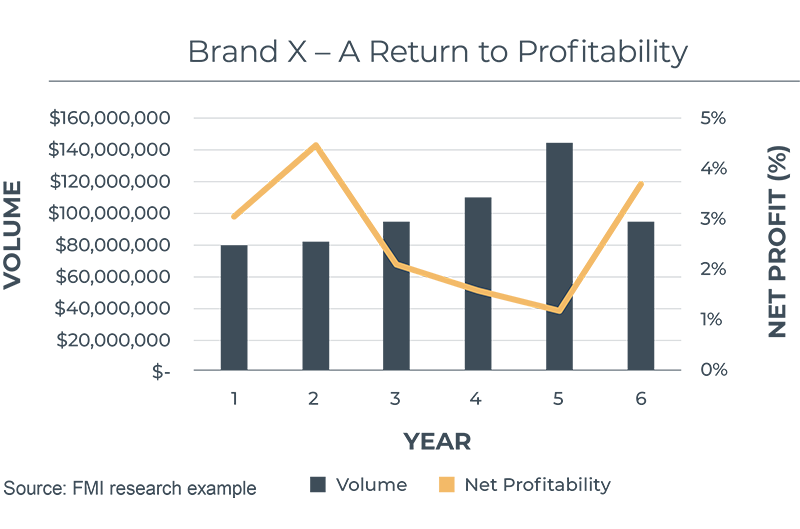

There are many correlations that show how a sharp increase in volume often has a deleterious effect on profitability. For instance, consider the following hypothetical case study that provides a broad framework of yearover- year growth when compared with profitability.

The situation illustrated here is extremely common in today’s world. Clients are flush with capital expenditure dollars and often supply construction organizations — general contractors and trade contractors alike — with more than enough opportunities to keep them busy.

However, the “governor switch” (or guardrails) for many construction firms is the ability to staff projects with the appropriate level of supervision as well as craftspeople. An interesting phenomenon occurs at this point: Many contractors will begin to price discriminate by increasing their bids, almost to deter a client from pursuing a project.

Contractors commonly believe that if they’re honest with a client about capabilities (or lack thereof), there may not be future opportunities. Along the lines of: “If we say no to them today, they’ll remove us from their bid lists. Plus, we’ve been chasing [INSERT CLIENT HERE] for X years…” But then when the deterrent fails, our contractor is left with the dubious challenge of building more, with fewer resources.

The Cost of Rapid Expansion

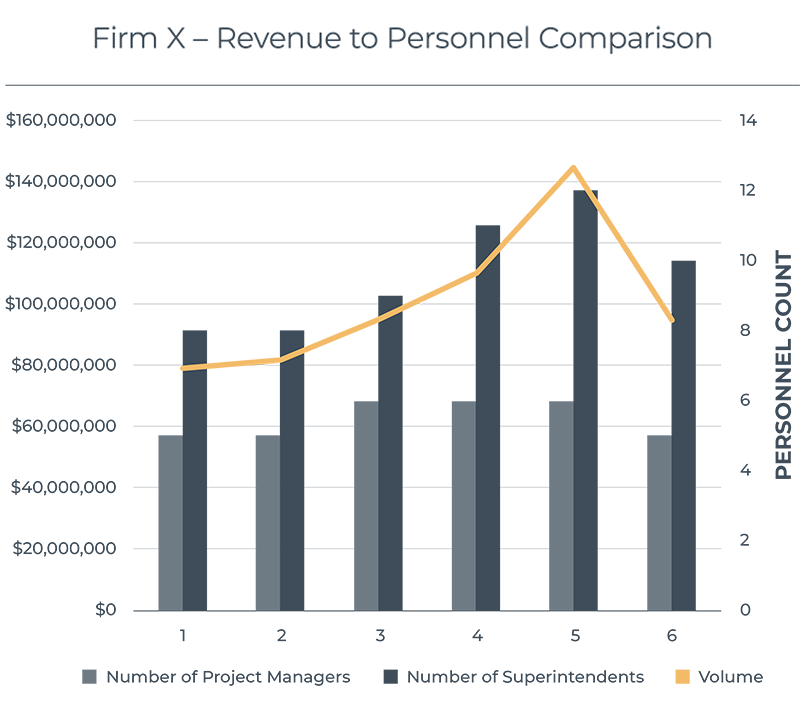

That said, it’s a bit myopic to examine this case by only looking at lost profitability. Below is an illustration of how our hypothetical firm might have addressed the management personnel ranks.

As shown above, the organization managed to grow in lockstep, expanding its teams as projects were added. Furthermore, this hypothetical organization didn’t have codified parameters within which to govern the management and supervision of projects. Put another way, new team members were added as “free agents,” bringing whatever set of best practices they had observed at their previous employer. Sure, they may have had newer software programs, but these tools weren’t utilized consistently. Additionally, the screening of new personnel was viewed through a lens of “right fit now” versus “right fit for the long term.” Using a sports analogy, personnel were inserted regardless of capabilities, with a “next person up” mentality.

Building a Sustainable Workforce

One important distinction is that a sports team generally has bench depth. In professional football there are likely three quarterbacks, with two of them representing the backup and junior understudy. Comparatively, construction organizations — particularly the hypothetical firm in our example — have no bench strength.

Of course, the first argument is that a professional sports team has a substantial payroll compared to most construction organizations, which would be a fair characterization. Additionally, there are likely support team members such as project engineers, foremen and assistants who are also supervising and managing people.

The firm in our example did have a small group of newer team members. However, this junior corps was hired reactively and immediately dropped on-site to fulfill project needs. Consequently, internal project team attrition was high, exacerbating a fragile personnel situation.

Common descriptions of the firm’s current state:

- “If we lose [INSERT PERSON HERE], we’re in trouble. They were going to run [INSERT PROJECT HERE].”

- “Everyone you work with does it slightly differently, which creates a challenge when we have to shift personnel around. You’ll spend half your time relearning project management 101 with your manager or superintendent.”

- “We throw people to the fire/wolves/deep end of the pool. Throwing them into the fire doesn’t seem right, but we have no choice.”

- “Our client loves [INSERT PERSON HERE]. Unfortunately, we’re worried that [INSERT PERSON HERE] is a flight risk. When they leave, so does that revenue.”

Remember that if an organization isn’t focused on creating a stable environment for its most critical asset, it’s building on a fragile house of cards. Still, there’s a lot to be said for how our example organization has approached strategic growth. Consider the following:

- Build internally and then grow. In a classic portrayal of “the tail wagging the dog,” our case study demonstrates a willingness to add volume and then add staff reactively. Comparatively, what if the firm had cultivated among staff a willingness to absorb cost, or at least spread the cost of additional personnel over a longer period? Personnel could have been added with the intention to grow and to prioritize the development of those individuals. For example, recognizing the cost of a project manager (say, $100,000) over time while consciously developing that individual versus parachuting in a new associate who might make a costly mistake with a project or critical client, possibly accounting for over $100,000 in expenses? There are certainly no guarantees — and there are situations in which free agency has benefited a firm. However, it’s highly probable that a misdirected hire will end up costing a firm, with little or nothing to show for it.

- Create discipline around decision making. What if our hypothetical organization had built with discipline? For instance, what if growth decisions were made using analytical tools that weighed factors such as current backlog, current staffing, profitability probability, etc.? Go/no-go decision making shouldn’t serve as the only mechanism by which a firm decides to chase opportunities. They should adopt a fact-based decision-making process that accounts for internal variables that can help firms grow profitably. It is safe to assume that clients or project owners be disappointed when a firm opts out of a bid or proposal. However, it is also likely that they will express gratitude for setting a project up for failure by not meeting expectations or causing undue stress to said customer in the long term.

- Build the correct firm-wide model of operations. It is imperative that firms have a consistent and proactive operational model. This is not to be confused with “personalities” or “management styles”; rather, it’s a methodology for preconstruction strategy, resource use, change order management structure, financial acumen, project execution at the conclusion of projects, etc. One of the best ways to gauge operational consistency is to ask the team, “How many different meeting agendas do our project managers and superintendents have for [INSERT MEETING HERE]?” If leadership hears, “Well, it depends on who you work with,” it’s likely time to consider refining the operational playbook.

- Build institutional training and rigor. Firms must have a system for introducing and training teams on the Brand X Way of Doing Things, and there must be discipline around managing that system to drive firm-wide adoption. This is not only to create internal accountability but also to drive people to do things correctly. For instance, firms that design effective onboarding practices that are longer than a single day are more likely to see buy-in to the institutional model, leading to long-term success.

Ultimately, one great question that every leader should ask themselves is this: If you hired a new team member today, would they simply represent a new project that your firm could take on, or do they represent future bench strength? Put another way, does posting on social media for a new superintendent backfill an already depleted roster? Many firms are running a deficit rather than creating an internal surplus of talent.

The Discipline of Operational Excellence

Consider again our case study example. Let’s say that in the past year — the year in which the firm regained profitability — there was an internal shift toward the aforementioned discipline. Rather than add volume, the firm strategically committed to both less volume and greater operational discipline. By taking this approach, the firm experienced several benefits.

- Quality NOT Quantity: Rather than chasing every opportunity, they increased the profitability of the right opportunities.

- Risk Profile: Making less money on more volume is a risky proposition. In what’s regarded as one of the riskiest industries in the world, making more money on less volume is the only strategic decision.

- The Brand X Way: By establishing a replicable model, this organization was able to identify the levers of success, enabling greater control in their projects.

- Magnet for Talent: Brand X was able to reestablish itself within its market as a top employer — much better than the “people mill” it had previously been tagged as.

- Client Loyalty: No client likes to be told no, but this organization was able to creatively sell itself better for long-term opportunities rather than resemble a bobblehead doll, accepting everything that came its way, only to underperform.

Strategic Growth for Lasting Profitability

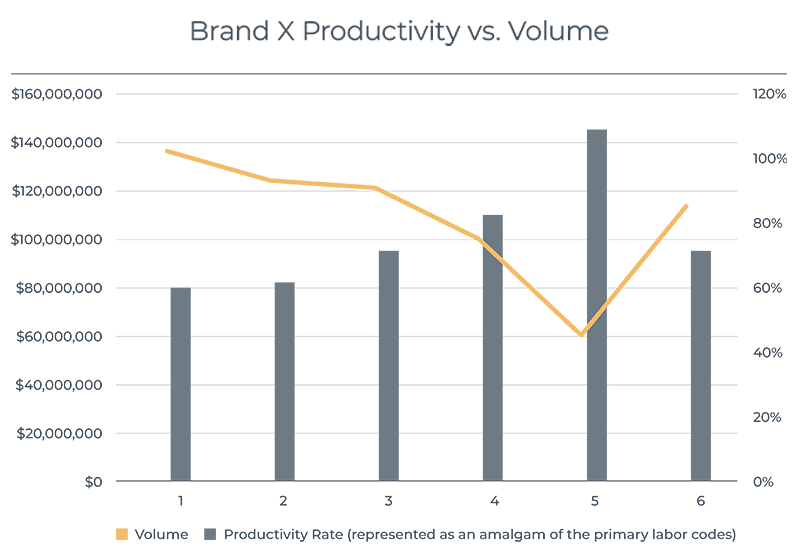

Lastly, for our case study let’s look at the impact of management and supervisory personnel on overall profitability. What if this were to also include a component of self-performing labor? For instance, what if each superintendent were also responsible for three to five foremen that may lead crews of labor or fleets of equipment? This would add a layer of complexity as illustrated in the graph below.

As the firm’s revenue increased over a six-year span, there was a precipitous drop in overall productivity across the major labor codes the firm uses. Many organizations would’ve chalked this up to an estimating error or contributed the decline to some external factor like the weather or permitting. There are often many factors involved, but there is another more insidious series of factors in play. As an example, a project was bid at an astounding 51% gross margin! The primary factor for the high bid-day margin was the lack of resources to complete the work were no crews on staff. So, rather than disappoint the client, an exceptionally high price was floated in an effort to “scare off the client.” Rather than scaring them off, the client accepts the high-priced proposal, much to the chagrin of the contractor.

Fast-forwarding to the conclusion of the project, the final gross margin was 11.2%, with an overhead of 9.5%. The 40%+ write-down would end up being attributed to crew shuffling, lack of adequate supervision focus, zero planning and an inherent belief that the firm had “enough padding” in their bid. However, what if a catastrophic accident had occurred, all to make a meager 1.5 net margin? Would it have been worth it then? Additionally, what was the impact on customer satisfaction and confidence as the company saw underwhelming performance day in and day out?

Of course, if every firm could know its revenue in advance and if the market were to participate as planned, this would all make for an easy endeavor in strategic planning and forecasting. Returning to profitability, however, may mean a return to realism with regard to a firm’s strategy, marketing, talent development and operations. And creating bench strength is more than simply having one extra manager on deck. Rather, it’s a strategic push to develop the correct foundation to build successfully for the long haul.