Walking the Corporate Board Compensation Tightrope

How to effectively balance recognition and rewards with independent board governance.

Common leadership principles regularly cry out against surrounding oneself with others who are too agreeable—the quintessential yes men and women. Such a team structure tends to lead to “group think,” diminished creativity and risk taking, pursuit of ideas without proper planning, and outside suspicion that leaders lack confidence, competence or worse. So what is the solution when yes men or women are in positions intended to serve as the company’s watchdogs?

Following the financial crisis and the implementation of Dodd-Frank Act rules, boards of publicly traded firms had to be composed of knowledgeable, independent directors who can be responsible fiduciaries. However, for privately held companies—which represent the vast majority of American engineering and construction (E&C) firms—it is more common to have inside directors and less likely to have subject matter experts within defined board committees. These factors, combined with uncertainty over how to compensate directors, can lead to ineffective board leadership.

Board Composition in the E&C Industry

In the E&C industry, companies report having eight or nine board members, on average, regardless of ownership structure. Those numbers correlate with the company’s size; that is, the larger the organization, the more members on the board.

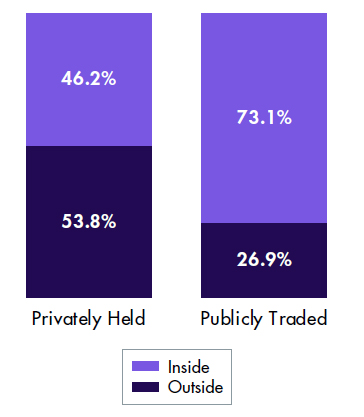

Among privately held companies, there are generally more inside directors—often employees, employees’ relatives and others with a deeply vested stake in the business—in comparison to publicly traded firms. Exhibit 1 shows that inside directors are usually a majority in private construction firms (versus a clear minority within public companies). The primary U.S. securities exchanges require that a company’s independent directors make up a majority of the board.

Exhibit 1. Inside vs Outside Directors

Source: FMI’s Executive Compensation Survey

Because compliance with federal regulations is significantly less for private companies, these E&C companies are frequently more relaxed in their board practices. For example:

- Private firms hold fewer meetings: an average of 4.2 per year as compared to 5.6 in public firms.

- Private firms are slightly less strict in requiring board attendance at meetings: 44% of privately held contractors have mandatory board meetings, while 50% of publicly traded companies do.

- Larger private firms report having established committees, but do not necessarily follow the same rigor when creating committees or selecting members. For example, most privately held firms lack a nominating and corporate governance committee, and most do not have 100% independent audit and compensation committees (required for trading on the NYSE).

Looser policies related to board and committee composition and meetings do not necessarily suggest that a company is more at risk or that performance will diminish over time. Many closely owned firms, in which owners and family members are the sole board members, have been successful through multiple generations. However, there is increasing evidence to suggest that diversified board membership can enhance financial performance.

Engineering and construction firms must weigh some critical factors when adding new outside directors to their boards—not the least of these is how best to compensate them. It is very unusual to provide compensation to inside directors for their board participation (as opposed to their employment with the company). FMI’s survey results show that fewer than 5% of contractors provide any compensation to inside directors. Outside director compensation must be competitive to attract well-qualified individuals. And to avoid questions of independence and reinforce responsible actions for the company’s benefit, that compensation must be reasonable.

Board Compensation: Fresh Insights

Outside board member compensation may be composed of some mix of the following:

- Retainer. Fixed payments to directors as compensation for their services, annual retainers are provided without regard to actual contribution or meeting attendance. There is a perpetual pendulum swing between annual retainers and meeting fees as the primary component of board compensation. While retainers tend to be more attractive to prospective board members, meeting fees more clearly convey the expectation that meetings be attended.

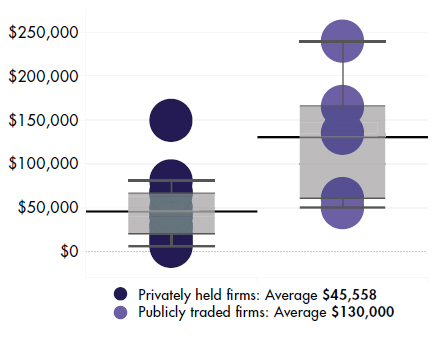

Only one-third of large E&C companies (i.e., those reporting over $500 million in revenue) participating in FMI’s Executive Compensation Survey pay an annual retainer to outside board members; the median retainer is approximately $62,000. Retainer amounts vary widely from company to company and are impacted by whether a firm is privately held or publicly traded, as shown in Exhibit 2.Not surprisingly, the median retainer among smaller companies is notably less, at approximately $20,000.

- Meeting Fees. “Pay for participation” is a common way to compensate board members for their attendance at board and committee meetings. These fees may be combined with a retainer or compose the only form of cash compensation to directors. Meeting fees encourage meeting attendance, but given the fiduciary responsibility that members are expected to uphold, attendance should be—and for many companies is—a requirement of the position.

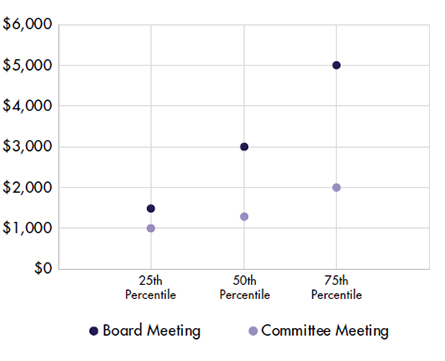

Additionally, premium fees are frequently paid for directors who serve as committee chairs. Committee chair premium fees are generally 25% to 50% of the standard meeting fee. Likewise, the board chair often earns a similar premium over the board meeting fee paid to other members if there is not a separate retainer paid to the chair.As shown in Exhibit 3, there is relatively little variance across construction firms in meeting fee amounts, both for board meetings and committee meetings.Exhibit 2. Average Annual Retainer Paid

Source: FMI’s Executive Compensation Survey

Exhibit 3. Outside Director Meeting Fees

Source: FMI’s Executive Compensation Survey

- Perquisites. There was a time when directors regularly received health insurance coverage, participated in supplemental retirement programs, were reimbursed for first-class travel, and were offered subsidies for outfitting offices and the like. These benefits are taxable, so many companies also provided additional compensation to board members to cover taxes. Perquisites have been largely eliminated in the face of greater regulatory and public scrutiny. Currently, most companies only cover board members for travel expenses to and from meetings.

- Incentive Compensation. Frequently paid on a discretionary basis, incentive compensation to outside directors is often reserved for annual bonuses, which tend to be quite small relative to total director compensation. This helps board members focus on the long-term trajectory of the company instead of short-term performance.

When a company has a long-term incentive plan or similarly structured equity-based award plan, outside directors are commonly included in the program. According to FMI’s survey results, nearly 40% of contractors offer long-term incentives to board members, which may be composed of cash, stock, synthetic equity or some combination thereof. The vesting period is often aligned with a regular board term—typically three to five years.In some instances, the grant of equity may support broader ownership guidelines. Only 18% of contractors currently require outside directors to have (or to work toward) a minimum level of ownership in the company, and it is a gradually increasing provision. The objective is much like the rationale behind providing equity or other long-term incentives to executives—to better align behaviors and interests with those of shareholders. For companies with formal ownership guidelines for outside board members, the most common requirement is that equity equal to three times annual compensation be accumulated within five years of being elected to the board. For companies that are not inclined to dilute ownership, the requirement may be satisfied through phantom stock or similar deferred compensation arrangements.

Looking for a Consistent Board Compensation Approach

One recent survey of private companies, of which slightly more than half were family-owned, reported that 95% had seen earnings increase since introducing formal boards. In the survey, boards were evenly split, on average, between inside and outside directors. The evidence of improved financial performance as well as better oversight for governance and compliance activities and additional expert guidance on operational matters are compelling reasons for a company to establish and maintain a board of directors.

As companies diversify their boards and add outside directors, a consistent approach to board compensation becomes an imperative. A plan for compensating board members helps attract qualified individuals and encourages the desired fiduciary and advisory activities. To develop a board compensation program, the company’s shareholders should consider the following factors related to outside directors:

- Background and Experience. What are the characteristics of an ideal director candidate, and how prevalent are such candidates? Among publicly traded firms, there is a requirement for topical expertise, specifically on the audit committee (but also highly encouraged for the compensation committee unless an independent consultant or similar advisor is engaged). Beyond committee-related knowledge or experience, a company may find value in securing one or more independent board members who have industry experience or familiarity with the corporate structure. For example, a privately held company that is considering converting to an employee stock-ownership plan (ESOP), or is already partially employee-owned, may find it beneficial to attract a board member who is an executive of an ESOP.

A board member’s background and/or unique skill sets will determine the competitiveness of his or her compensation. For instance, shareholders could simply elect a local banker to the board to provide financial guidance and oversight, or they could select a partner of a Big Four accounting firm with significant industry experience. It is fair to assume that the latter would expect a higher board compensation package. That said, there is a strong bias toward placement of CEOs and existing directors on boards. Therefore, a company may take a more conservative board compensation structure and still reap the benefits of an independent, sophisticated board by identifying highly qualified candidates who serve in non-CEO leadership roles and who have little or no prior board experience.An important feature of board compensation is that, beyond differences in their level of participation, all outside directors are to be treated equally. Retainers, meeting fees and any other compensation elements are the same amounts across all directors and only differ based on meeting attendance and service on a committee or as a chair.

- Performance. Develop a position description or similar outline of director responsibilities. Much like a traditional employee job description, this document sets clear expectations related to the role and provides shareholders with a tool that they can use to hold directors accountable. There is a trend among privately held companies to bring on independent directors who seem to become “irreplaceable,” in that their performance is not reviewed and their terms are renewed by default. Companies must evaluate board performance to maximize return on investment in board compensation and to recoup the costs incurred in recruiting members and implementing initiatives at the board’s direction. In fact, in a recent study conducted in collaboration with the Construction Industry Round Table, FMI’s research team found that boards that evaluate their individual directors have a mean effectiveness rating of 8.1 out of 10 compared to those who do not at 7.3 out of 10.1

At a minimum, a board should speak to efforts and results at an annual shareholders meeting. More progressive companies use performance reviews to evaluate each individual board member, pursuant to the position description and on a routine schedule. From a performance perspective, board compensation can be aligned closely with employee compensation; if a director is not meeting expectations (e.g., by not actively participating on an assigned committee), then why should a company continue to pay a retainer or recognize contributions (or in this case, the lack thereof) through a long-term incentive award?

- Fiduciary Charge. Board members must act on behalf of the shareholders with regard to primary business matters. This need to “think like an owner” is the primary reason that equity, or equity-like, long-term incentive compensation (e.g., phantom stock or stock appreciation rights) is awarded to independent directors. There is heightened interest across the E&C industry in long-term incentive plans, but in today’s economy, the chief focus of these plans is often the retention of key leaders rather than the advancement of shareholder interests. While both objectives are critically important, shareholders’ goals for the ongoing success of the business may have greater impact on long-term positive performance. As independent advisors, outside directors are also uniquely positioned to observe the maintenance of company culture and values more objectively and safeguard against imbalanced employee compensation programs that may lead to unintended consequences.

Because of this, including key employees and outside directors in a long-term incentive program—particularly in companies where equity grants are not an option—can be highly effective. Board members are less likely to simply “rubbber-stamp” executive actions when they have both a fiduciary responsibility and a personally vested stake in keeping the company on the right track. Long-term incentives to both executives and directors should always align with the activities that most positively impact company performance and keep it on the path to continuous financial success.

Finally, there are many ways to tackle effective board compensation. Contemplate the following four key areas to get started with a successful program:

- Consider the impact and effect of an independent board, and understand that a board means gaining additional oversight, expertise and advice—not owners forfeiting control.

- Determine the right fit for new board members: Document the knowledge, skills and demographics that are best-suited for the company.

- Establish the approach to board compensation based on how aggressive or conservative the firm wants to be in attracting qualified talent and what tools might be most appropriate to reinforce multiyear alignment with shareholders.

- Begin the outside director recruitment process!

1 2018 FMI/CIRT Corporate Governance Study. FMI. September 2018.